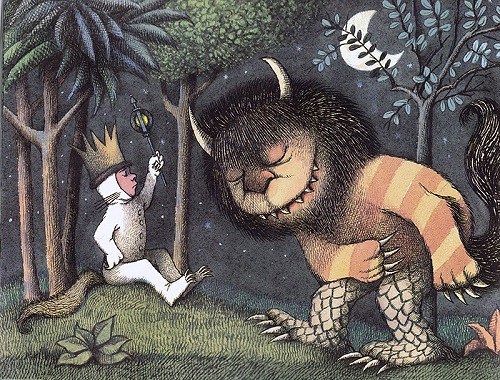

I can’t wait to check out the Maurice Sendak exhibit at the Society of Illustrators. Today seemed like the perfect time to share one of the most inspirational letters I’ve ever read from his editor the legendary Ursula Nordstrom addressing his letter sharing some doubts about his own capabilities as a writer. Two years after this letter was written, Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are — edited by Nordstrom — was published.

via Letters of Note:

August 21, 1961

Dear Maurice,

I’ve been out of the office with a bad throat and assorted aches, which is why I haven’t written you before. Also I spent the entire day Saturday writing you a big fat long-hand letter about Tolstoy, Life, Death, and other items which you can get at your friendly Green Stamps store. And then I left it at home. Will now send the gist of what I think I wrote, and it will be more legible than my handwriting anyhow.

OK about the Zolotow book, of course. We’re sorry but she is so glad you’re illustrating it, and so are we, that nothing can cloud our pleasure.

I was glad to have your note about the Doris Orgel story. She is making a few changes which she thinks will improve it, and it will really be a charming book and quite original. She came to see me. Isn’t she an interesting person? I was much impressed with her, and I was irritated all over again with myself for not having been enthusiastic about Dwarf Long Nose.

Your cabin by the lake, and your own boat, sound fine. Please remember that the moon will be full on Friday, the 25th, and take a look at it. It should be beautiful over Lake Champlain.

I loved your long letter and hope it clarified some things for you to write it. Sure, Tolstoy and Melville have a lot of furniture in their books and they also know a lot of facts (“where the mouth of a river is”) but that isn’t the only sort of genius, you know that. You are more of a poet in your writing, at least right now. Yes, Tolstoy is wonderful (his publisher asked me for a quote) but you can express as much emotion and “cohesion and purpose” in some of your drawings as there is in War and Peace. I mean that. You write and draw from the inside out—which is why I said poet.

I was absorbed when I read you had “the sense of having lived one’s life so narrowly—with eyes and senses turned inward. An actual sense of the breadth of life does not exist in me. I am narrowly concerned with me… All I will ever express will be the little I have gleaned of life for my own purposes.” But isn’t that what every fine artist-writer ever expressed? If your expression is now more an impressionist one that doesn’t make it any less important, or profound. That whole passage in your letter was intensely interesting to me. Yes, you did live “with eyes and senses turned inward” but you had to. Socrates said “Know thyself.” And now you do know yourself better than you did, and your work is getting richer and deeper, and it has such an exciting, emotional quality. I know you don’t need and didn’t ask for compliments from me. These remarks are not compliments—just facts.

The great Russians and Melville and Balzac etc. wrote in another time, in leisure, to be read in leisure. I know what you mean about those long detailed rich novels—my god the authors knew all about war, and agriculture, and politics. But that is one type of writing, for a more leisurely time than ours. You have your own note to sound, and you are sounding it with greater power and beauty all the time. Yes, Moby Dickis great, but honestly don’t you see great gobs of it that could come out? Does that offend you, coming from a presumptuous editor? I remember lines of the most piercing beauty (after he made a friend there was something beautiful about “no more would my splintered hand and shattered heart be turned against the wolfish world.”) But there are many passages which could have been cut. But I wander…

You wrote “my world is furniture-less. It is all feeling.” Well feeling (emotion) combined with an artist’s discipline is the rarest thing in the world. You love and admire the work of some other contemporary artists and writers today but really, think how few of them have any vigorous emotional vitality? What you have is RARE. You also wrote “Knowledge is the driving force that puts creative passion to work”—a true statement, and also very well put. But it would include self knowledge for some as well as knowledge of facts for others. (Is this English I’m writing? I need an editor.)

You reminded me that you are 33. I always think 29, but OK. Anyhow, aren’t the thirties wonderful? And 33 is still young for an artist with your potentialities. I mean, you may not do your deepest, fullest, richest work until you are in your forties. You are growing and getting better all the time. I hope it was good for you to write me the thoughts that came to you. It was very good for me to read what you wrote, and to think about your letter. I’m sorry you have writers cramp as you put it but glad that you’re putting down “pure Sendakian vaguery” (I think you invented that good word). The more you put down the better and I’ll be glad to see anything you want to show me. You referred to your “atoms worth of talent.” You may not be Tolstoy, but Tolstoy wasn’t Sendak, either. You have a vast and beautiful genius. You wrote “It would be wonderful to want to believe in God. The aimlessness of living is too insane.” That is the creative artist—a penalty of the creative artist—wanting to make order out of chaos. The rest of us plain people just accept disorder (if we even recognize it) and get a bang out of our five beautiful senses, if we’re lucky. Well, not making any sense but will send this anyhow.

Hope the rest of your vacation is wonderful. I’ll see you when you get back. And thanks again for writing.

Ursula

You know one of these days you’ll go back to Old Potato, or a version of that situation, and it will have “cohesion and purpose” and will have so many universal emotions within its relatively simple framework. Love, fear, acceptance, rejection, re-assurance, and growth. No more for now.